CODA

Bach Cello suite in C minor

Who loses its culture, loses himself

Mario Vargas Losa

Ensemble

Project Manager / Director: J.U.Lensing

Choreography: Jacqueline Fischer

Music: Johann Sebastian Bach / Thomas Neuhaus

Video: Tobias Rosenberger

Cellist: Beate Wolff

Dancers / performers: Nina Hänel, Phaedra Pisimisi

KBB: Claudia Bisdorf

Costumes: Caterina Di Fiore

Scenography: J.U. Lensing

About the Production

The THEATER DER KLÄNGE has been working for several years with intermedia forms of dance, electronic music and interactive live video.

As a continuation of the electronic-intermedia works HOEReographien and SUITE intermediale, a new work entitled “CODA – Bach’s Cello Suite in C Minor” has been developed for the 2013/14 season.

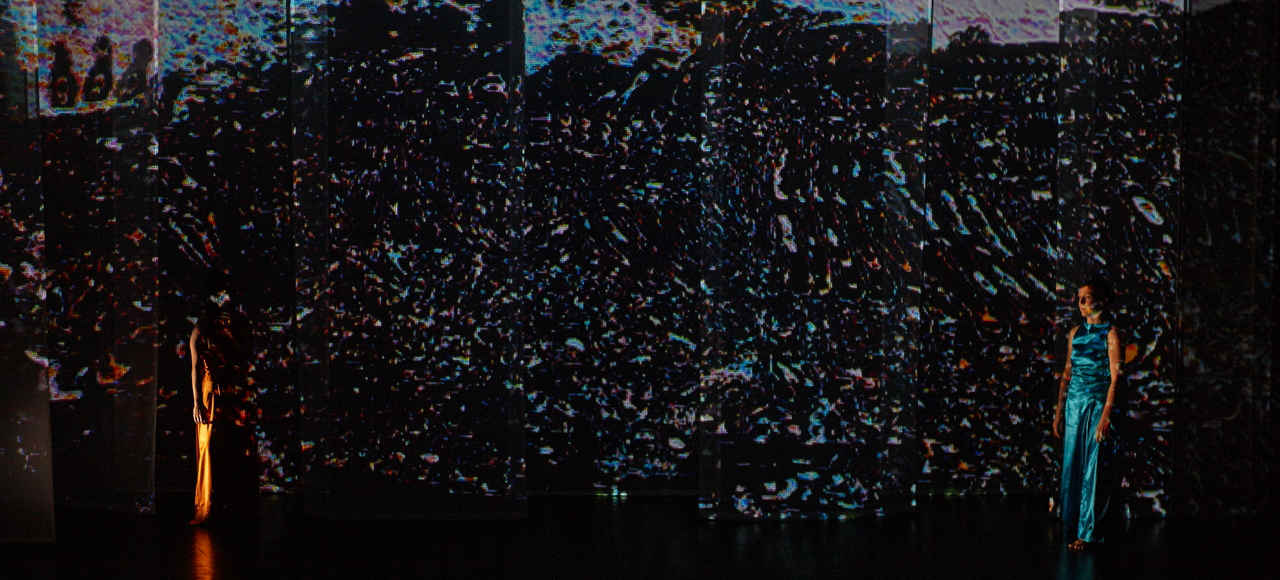

The focus of the work in CODA was on the dancing interaction possibilities with light and video.

J.S. Bach’s music – and especially the dance-cello suites – are in themselves a work of variation on dances that were “old-fashioned” in their time. Bach uses the possibility of going beyond the practical purpose to expand, vary and contrapuntally reflect on dance forms still known at that time. Taking up this approach and continuing it with today’s staging and musical means, a visual music in the structure of Bach’s music was created for the six cello movements by Bach through dance and composed light.

The baroque music inspires references to the very geometric dance forms of the baroque, as well as to ornamentation in light, which in turn uses the dancing body as a moving image surface. Thus a very sensual, history-bridging work of art was created, consisting of dance to Bach’s cello music in a very modern, moving light implementation based on Baroque dance forms such as Allemande, Sarabande or Gigue.

In the second part of the program the 6 dance movements of the Cello Suite were repeated. In the repetition, however, the dancers, through their movements, were at the same time musicians of an electronic music, which takes Bach’s music as its musical material, which is played electronically through movement dynamics. The resulting media music also directly controlled the interactive video presentations of the theater scenography, which in turn quotes baroque scenic approaches.

CODA: Press

A pop star called Bach

(…) At the start, the stage belongs to the cello player Beate Wolff. She takes a seat with her instrument on the left hand side and concentrates to play Bach’s Cello Suite, accurately and true to the original.

After a few minutes, the two dancers appear: Nina Hänel and Phaedra Pisimisi. They begin transforming the sounds.

Notes become movements, then images appear. With their own light, the women’s feet paint lines along the floor. Their steps are taken from the courtly dances of the Suite; Sarabande, Allemande, Courante and Gigue. First they draw out austere geometric Forms; then they are joined by flourishes, loops and ornaments, all elegantly played out. A marvellous sight to see and this is a small miracle. If anyone ever doubted that Baroque music could be painted, they must now face the overwhelming proof. At the end of the first act, the light billows like the dancers’ tutus; flowing and waving, flickering up the walls like fire. A fiery sea of red and gold.

The evening stands up bravely against the pace of modern life. There is something dazzlingly aesthetic about it. It is calm, manipulative, almost hypnotic. But the reason why it is called Coda only becomes clear in the second act after the interval. Coda, which actually means “tail” in Italian, marks the final notes of a musical composition, the act that rounds up a work at the end.

Cello player Beate Wolff takes a break. Now the music comes from the loudspeakers: electronic beats, fast but not hectic. Sounds and movements are transfered onto the stage background in the form of opulent images. Every once in a while, you can vaguely discern walls of light, perhaps a church. One’s view follows a hallway into an open garden.

Amazing: what we are listening to is still Bach, played to the limits of the technically possible. And then the old gentleman finally becomes our own contemporary:

Bach the pop star; wild, free and modern.

Petra Kuiper

Neue Rhein Zeitung

Video art to the music of Bach

In its new play, the Theater der Klänge (theatre of sounds) dedicates itself to the musical heritage of Johann Sebastian Bach and to the dance forms of the Baroque. At first one feels transported into a courtyard; the dance is respectful conversation, expression and etiquette. But all that changes quickly. Curving movements come flowing in. The dancer are experimenting. They are supported by light, projecting onto the stage in a variety of patterns. One time only their arms stand out, the rest of their body remaining in darkness.

The makers of “CODA” play skilfully with the images, which are produced by light and shadows. And so, a surreal world emerges before the eyes of the spectators. A world in which the dancers take on the form of icebergs or pendulums.

It becomes even more drastic in the second act of the play. The tones are wilder, the sounds of Bach become alienated and stretched out electronically. It begins with an echo of cello music and extends into an insect-like buzz. At one moment, a great storm builds up. Then the music seems to describe a roaring river. It is sometimes unsettling but well played out.

The video images cast onto the stage produce the effect of a feverish dream. Room constants follow their trails. The feeling becomes palpable almost to the point of dizziness. The dancers appear first as captives and then as conquerors of the light and of the rays engulfing them like a net.

It is not an easy endeavour. Coda casts its view onto a derailed world. There is no cure for confusion. The closing moment is brought by an outburst of flames into which the dancer vanishes. The public applauds in loud appreciation.

Verena Patel

Rheinische Post

The lost symmetry

Johann Sebastian Bach as ballet composer – a more striking contrast is hard to imagine. But for all that, many of his works were the foundation for choreographies. John Neumeier has even taken the “St Matthew Passion” to create a famous dance theatre evening with the Hamburg Ballet. Now Theater der Klaenge brings to Dusseldorf the Cello Suite in C minor with two dancers on stage. “CODA” is the name of the play.

The evening begins like a chamber music concert. Cello player Beate Wolff comes on stage, takes a short bow and plays the prelude of Bach’s Cello Suite in C minor. Only after the following phrases do two dancers appear, dressed entirely in white, with measured steps. Their feet seem to leave footprints on the stage floor behind them; video projections, played into their movements in real time. A symmetrical pattern emerges on the floor, following the ballet notations of choreographer Raoul-Auger Feuillet. What we know of the Baroque dance style today is largely owed to his writings, which appeared in the early 18th century.

An ensemble with the urge to explore

Research into historic theatre forms is a fundamental interest of Theater der Klaenge in Dusseldorf. The ensemble has recently celebrated its 25th birthday. The title of the new play “CODA” is also a cross reference to the history of the group. It is a pending state, something that is still to be said, played and danced, after many plays in which intermediality is brought to the foreground. Theater der Klaenge has not engaged in pre-existing music for quite some time. Bach’s cello suites attracted director Jorg U. Lensing because the titles of the phrases cite Baroque dances, although they are not dance music themselves.

Just as Bach mused on the dances of the Baroque period and changed their character, today the Theater der Klaenge works on the Cello Suite.

After a first run, they take a short break. Then it’s the soloist’s turn again. This time her instrument is amplified electronically. And not only that: echoes, sonic reflections and distortions unfold. Composer Thomas Neuhaus sits in front of his computer and mixes the sounds to the player’s cello music in real time. The material has been set down but there is also room for improvisations. The musician and the man with the laptop react to each other. Even the dancers, using their movements, can influence the recording in Jacqueline Fischer’s choreography.

Breaking down Baroque

Baroque forms are broken down. Video artist Tobias Rosenberger gets more active at every turn. His projections are the only light source; the theatre spotlights are left off. He casts images of bars bending like rubber over a lying dancer and then beams of light, like in a work of science fiction where spaceships attain faster-than-light travel. Now only a few parts of her body can be seen under the light: her hands, her face… The bodies of the dancers Nina Haenel and Phaedra Pisimisi become fragmented and then put together again. The images can not be rationalised or expressed in words. “CODA” is surely a complex and respectful confrontation between Baroque art forms and present times.

Stefan Keim

www.deutschlandradiokultur.de